Introduction

You have certainly experienced this: an instruction you thought was clear is not followed, or is partially followed, or in an unexpected way. Before concluding there is a comprehension or motivation problem, question yourself about the way you formulated your message. Because the manner of giving an instruction considerably influences its reception and execution.

People with Down syndrome have particularities in language processing that make certain formulations more effective than others. Understanding these particularities allows you to adapt your communication and significantly improve daily cooperation. This article offers you concrete strategies for formulating instructions that will be understood and followed, in sheltered workshops, residential homes, specialized institutes or support services.

Understanding Difficulties in Processing Instructions

Verbal Working Memory

Working memory is the ability to maintain and manipulate information for a few seconds, the time needed to use it. In people with Down syndrome, verbal working memory (which processes auditory information) is often more limited than visual-spatial working memory.

Concretely, a long instruction or one composed of several steps quickly overloads this memory. The person retains the beginning but loses the rest, or remembers the end but has forgotten the beginning. When you say "Go get the broom from the closet, then sweep in front of the entrance and then put the broom away," the person may only retain part of this information.

Processing Time

Processing auditory information takes more time for people with Down syndrome. When you speak, your listener must perceive the sounds, assemble them into words, understand the meaning of each word, grasp the sentence structure, deduce the overall message. Each of these steps takes a little more time.

If you quickly chain information or move on to something else without leaving a pause, the processing does not have time to occur. The person may appear not to be listening or not understanding, when they simply need more time.

Abstraction and Implicit Content

Instructions often contain implicit elements that we consider obvious. "Tidy your room" assumes the person knows what "tidy" means to us, which objects should go where, what level of tidiness is expected. These implicit meanings may not be shared.

Similarly, abstract or figurative formulations pose problems. "Be careful," "Be good," "Behave well" are vague instructions that can be understood in multiple ways or not understood at all. The person does not know concretely what is expected of them.

The Power of Short Sentences

One Idea Per Sentence

The fundamental rule is to limit each sentence to a single idea, a single action. Instead of the complex instruction cited above, break it down: "Go to the closet." (Wait.) "Take the broom." (Wait.) "Sweep in front of the entrance." This segmentation respects working memory capacities and allows step-by-step processing.

In practice, this breakdown requires a change of habit. We tend to condense information to be efficient. But this apparent efficiency backfires if the message is not understood. Taking the time to segment saves time on repeated explanations and corrections.

Rhythm and Pauses

Between each short sentence, leave a pause. This silence is not wasted time, it is the time necessary for processing the information. Count mentally to three or five before moving on, or wait for a signal from the person (look, nod, beginning of execution).

This rhythm may seem slow, especially when you are in a hurry. But remember that repeating a poorly understood instruction several times takes more time than giving it correctly once. And the repeated experience of incomprehension generates frustration and demotivation on both sides.

Verify Before Continuing

Before moving on to the next instruction, make sure the previous one is understood or being executed. This verification can be implicit (observe that the person begins the action) or explicit (ask to show, to repeat in their own way).

However, avoid the question "Did you understand?" which almost automatically generates an unreliable "yes." Prefer concrete verifications: "Show me where you're going," "What are you doing first?" These questions reveal real understanding without putting the person in difficulty.

The Power of Positive Formulations

Saying What to Do Rather Than What Not to Do

"Don't run" is less effective than "Walk." "Don't shout" is less clear than "Speak softly." This difference is not trivial. A negative formulation requires understanding the forbidden action, then mentally transforming it into its opposite. It is an additional cognitive operation that can fail.

Moreover, our brain tends to retain the mentioned action rather than the negation. "Don't think of a pink elephant" inevitably makes you think of a pink elephant. Similarly, "Don't hit" may evoke the action of hitting more than the intention to forbid it.

Describe the Expected Behavior

Move from vague prohibition to precise desired behavior. Instead of "Stop making a mess," say "Sit on your chair." Instead of "Be nice to others," specify "Speak softly to Marie." The person knows exactly what they should do, without having to guess.

This precision is particularly important in potentially conflictual situations. Inappropriate behavior is often the manifestation of an unsatisfied need or a misunderstanding. Proposing a concrete alternative offers a constructive way out.

Inclusive Formulations

When possible, include yourself in the instruction: "We're going to tidy together," "We're going to wash our hands." These formulations create an alliance, suggest that you will do the action with the person, reduce the perception of an authoritarian command.

The use of the collective "we" is particularly useful for group routines, transitions, moments when everyone's cooperation is necessary. It creates a sense of belonging and cooperation.

Practical Techniques for Effective Instructions

Capture Attention Before Speaking

An instruction given to someone who is not attentive is a lost instruction. Before speaking, make sure you have the person's attention: call them by their first name, wait for them to look at you, position yourself at their height and in their field of vision.

Eye contact is not always comfortable for some people. In this case, attention to the voice, a body orientation toward you may suffice. The important thing is that the person is receptive before you begin transmitting your message.

Accompany Words with Gestures

Gestures reinforce the verbal message. Pointing to the place to go, miming the action to perform, showing the object concerned: these visual and kinesthetic supports help understanding and memorization. They are particularly useful for people whose visual channel is their strong point.

If you use structured signs (Makaton or others), integrate them naturally into your instructions. "Put away" accompanied by the corresponding sign offers a double entry to the information. Even without a formal system, your natural gestures help understanding.

Use Visual Supports

For recurring instructions, a permanent visual support is more effective than repeated explanations. A sheet with illustrated steps, a visual schedule, pictograms indicating rules: these supports can be consulted at any time, as many times as necessary.

In sheltered workshops, visual job sheets allow the worker to refer themselves to the steps without asking again. In residential homes, a visual sequence of morning routines guides the person toward autonomy. These supports free the professional from repetition and empower the accompanied person.

Give Meaning to the Instruction

An instruction whose reason is understood is more easily accepted and memorized. "We put on the apron to protect your clothes," "We put away the tools to find them tomorrow," "We speak softly not to disturb others." This explanation gives meaning to the requested action.

However, be careful not to overload the message. The explanation should remain simple and come after the main instruction, not before or instead of it. The requested action remains central, the explanation illuminates it without drowning it.

Adapting Instructions to Context

In Sheltered Workshops: Work Instructions

In the professional context of the sheltered workshop, instructions often concern technical tasks. Break down each task into simple steps, create visual supports for recurring tasks, use demonstration before verbal explanation whenever possible.

Be particularly attentive to safety instructions. They must be formulated positively ("Wear your gloves" rather than "Don't work without gloves"), repeated regularly, visible in the work environment. Safety does not tolerate comprehension approximations.

Quality instructions also deserve particular attention. "Be careful" is not enough. "Check that the edge is straight," "Count the pieces before closing the box," "Look if the color is the same as the model" are verifiable and concrete instructions.

In Residential Homes: Daily Living Instructions

In residential homes, instructions relate to daily life, hygiene, collective living rules. They are often part of routines that, once established, require fewer explicit instructions.

For collective living rules, positive formulations are particularly important. "We eat together at the table," "We speak in turn," "We knock before entering" establish clear expectations without creating a climate of constant reprimands.

Instructions related to personal autonomy (hygiene, dressing, tidying) benefit from being accompanied by visual supports and progressively aiming for self-guidance rather than dependence on external reminders.

In Specialized Institutes and Support Services: Educational Instructions

With children and adolescents supported in specialized institutes or support services, instructions also serve educational objectives. They must be adapted to developmental age, not necessarily chronological age.

Playful formulations can increase cooperation: "Your hands are going to give a hug to the soap," "We play the silence game while we cross." However, be careful not to infantilize adolescents who need to be treated according to their age.

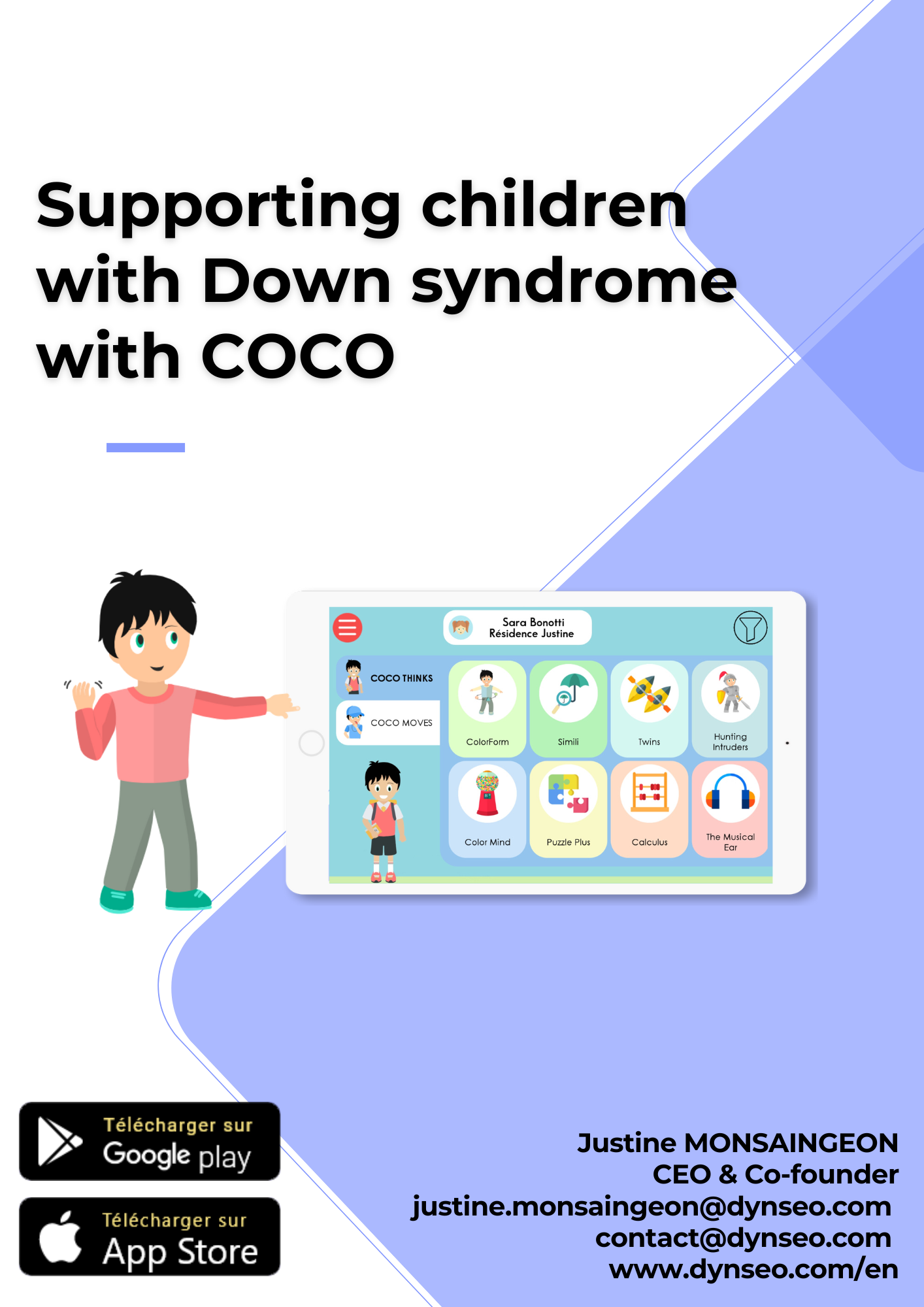

The COCO THINKS and COCO MOVES application, developed by DYNSEO for children aged 5 to 10, uses adapted and progressive instructions in its educational games. It can inspire your own formulations and show how clear instructions guide learning.

Managing Difficult Situations

When the Instruction Is Not Followed

Faced with an instruction not followed, resist the temptation to raise your voice or simply repeat. First ask yourself if the instruction was understood. Reformulate if necessary by simplifying, accompanying with gestures, showing.

If comprehension seems acquired but execution does not follow, question yourself about possible obstacles: is the person physically capable of performing the action? Are they tired, stressed, preoccupied by something else? Is there an environmental obstacle? Does the instruction conflict with an unexpressed need?

Repeating the instruction with patience, possibly accompanied by partial physical guidance, is often more effective than escalation in insistence.

When the Instruction Generates Opposition

Systematic opposition to instructions can signal several things: a need for control over one's own life, recurring misunderstanding, fatigue from constantly receiving instructions, an unsatisfied need expressing itself through refusal.

Offering choices when possible reduces opposition: "Do you want to put away the books first or the toys first?" The instruction is the same (tidy) but the person keeps a margin of control. This strategy must be used with discernment, because proposing choices repeatedly can also be exhausting.

Adapt to the Person's State

Comprehension and cooperation abilities fluctuate according to physical and emotional state. A tired, sick, anxious or disturbed person will have more difficulty processing instructions. In these moments, simplify even further, reduce expectations, prioritize the essential.

Recognizing these fluctuations and adapting your requirements is not laxity, it is realism. Insisting on complex instructions when the person is not in a state to process them generates failures that teach nothing and discourage everyone.

The Importance of Team Consistency

Harmonize Formulations

If each team member formulates instructions differently, the accompanied person must constantly adapt. This variability increases cognitive load and risks of misunderstanding. Agree as a team on standard formulations for recurring instructions.

This harmonization does not mean robotizing interactions. Each professional keeps their personality. But key instructions, important rules, routine steps benefit from being formulated consistently by everyone.

Transmit Effective Strategies

When you discover that a particular formulation works well with a person, share it with the team. "With Paul, I always say 'It's time to...' rather than 'You must...' and it works better." These individual observations, pooled, enrich collective competence.

Handovers, team meetings, individual files are opportunities to share these good practices. Continuing education also allows updating and perfecting the communication skills of the entire team.

Training as a Lever

The "Down Syndrome in Residential Facilities: Comprehensive Support" training offered by DYNSEO devotes a significant part to communication and adapting instructions. It allows understanding the foundations of these adaptations and practicing effective formulations together. A team trained together develops a consistency of practice beneficial for all.

Stimulating Comprehension Abilities

Beyond Adaptation: Progression

Adapting your instructions does not mean freezing the person's abilities. On the contrary, adapted communication reduces frustration and creates conditions for progression. When the person experiences success in understanding and executing instructions, their confidence increases, their motivation strengthens.

Gradually, you can slightly increase complexity: two steps instead of one, a slightly less explicit formulation, less gestural guidance. This progression must be very gradual and respect each person's rhythm.

Cognitive Stimulation

Cognitive stimulation applications like CLINT, developed by DYNSEO for adolescents and adults, offer exercises that work on instruction comprehension, working memory, attention. These playful tools usefully complement human support.

Short and pressure-free sessions of CLINT allow working on these skills in a repeated and motivating way. Progressive challenges adapt to each user's level, avoiding discouragement and boredom.

Key Takeaways

> Adapting your instructions for people with Down syndrome rests on a few key principles: short sentences limited to one idea, positive formulations describing expected behavior, sufficient pauses for processing, complementary visual and gestural supports. This adaptation is not an impoverishing simplification but a respect for cognitive functioning that promotes understanding, autonomy and well-being.

Conclusion

Formulating effective instructions is a professional skill that is learned and perfected. The adaptations presented in this article do not require sophisticated equipment, but a change of habits and constant attention to the way we communicate.

The benefits are considerable: fewer necessary repetitions, less frustration on both sides, more autonomy for the accompanied person, more time available for relationship and quality support. These communication skills are transferable to all situations and durably enrich your professional practice.

To deepen these skills and integrate them into a comprehensive support approach, discover the "Down Syndrome in Residential Facilities: Comprehensive Support" training offered by DYNSEO.

Internal Linking Suggestions

1. Communication and Down syndrome: understanding the comprehension/expression asymmetry

2. Pictograms and visual supports: creating an environment that facilitates communication

3. Signs and gestures to support communication in sheltered workshops, specialized institutes and residential homes

4. Recognizing signs of communicative frustration before overflow

5. Cognitive particularities and Down syndrome: processing time, memory, abstraction

Recommended Training:Down Syndrome in Residential Facilities: Comprehensive SupportRecommended Applications:

COCO THINKS and COCO MOVES (for children)CLINT, your brain coach (for adolescents and adults)